Moravec's Paradox, the "Boss" in the Path to AGI?

Sept 9, 2021 posted by Franklin Ren, revised on Nov 28, 2023

Scientists have been trying for decades to build robots that could perform physical tasks just like humans - robots that could learn to cook, drive, and assemble furniture together with minimum human supervision - but looks like we are still far from there yet. In the struggle of building such robots, a term comes out: Moravec's Paradox. In a simple description, what Moravec's Paradox is referring to is that tasks hard for humans - for example, chess, Go, and even math problems - are easy for AI, but tasks easy for humans - for example, vision, simple reaction, and body control - are extremely hard for AI. There are even several AI scientists claiming that the last milestone in the path to AGI, is not the Riemann Hypothesis or Unified Field Theory, but winning humans over in a football game.

Moravec's own explanation to this paradox seems to be simple: those “easy” skills for humans are developed from millions of years of evolution, and the strategies learned during our ancestors' interaction with the physical world have been encoded into our brain as a very abstract prior, which could help us to quickly adapt to new physical tasks. In contrast, those “hard” skills have only been there for less than a thousand years and are very new to our brains - our brains are merely not specialized for those tasks. Think about pigeons, pigeons are very good at memorizing locations since their brains are specialized in that task, even though they are not as smart as humans in almost all other tasks. If Moravec's explanation is true, decoding this abstract prior - or finding an easier alternative that could serve the same purpose - will be the hardest thing for AGI.

I don't want to talk about decoding this prior here - that is the job of neuroscientists - what I want to discuss here is how different AI scientists are trying to find that “alternative path”. One clear observation is that there is no way we could train from all the previous data our ancestors have seen - data from interactions with the real world are extremely costly to collect, so we need something else.

Is language the key?

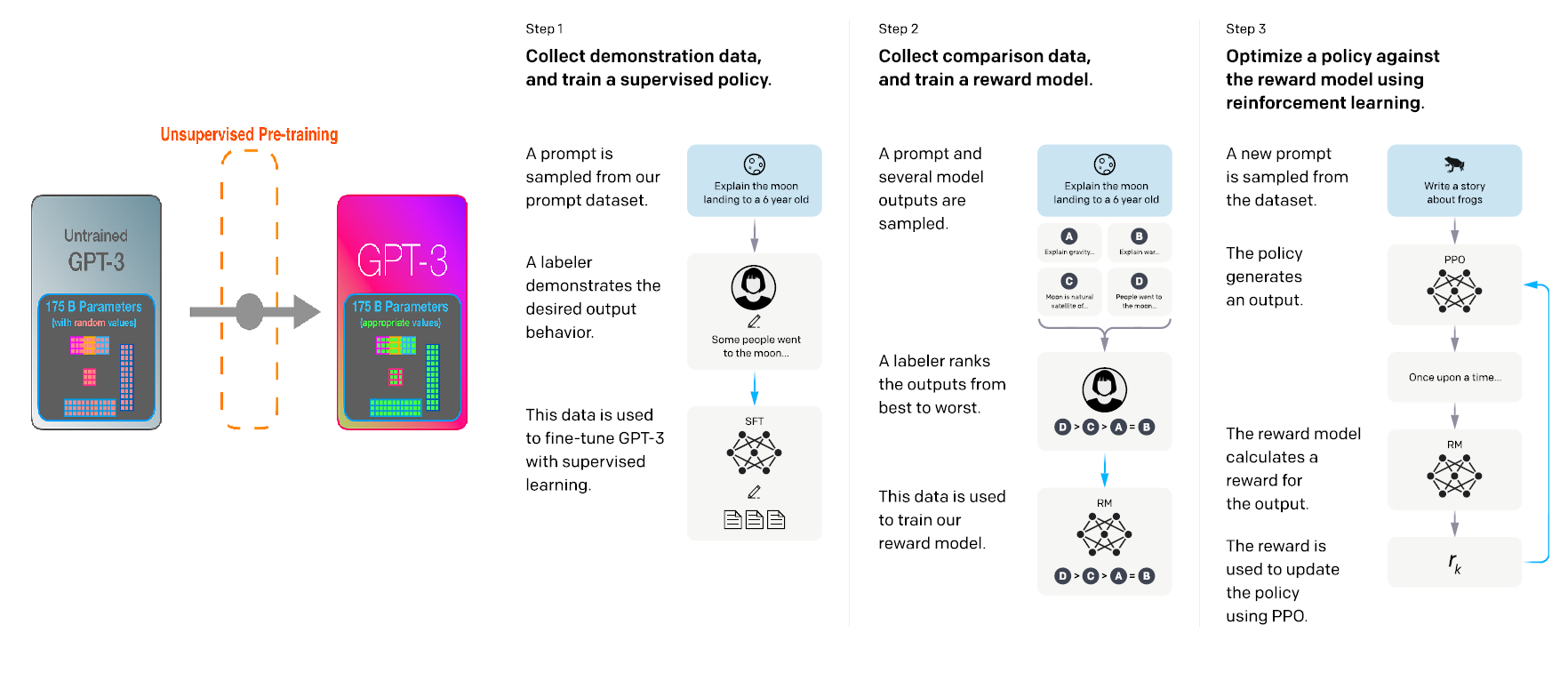

The most well-known approach at this time is OpenAI's GPT series, proposed by its chief scientist Ilya Sutskever. The key idea is to use language as a medium to connect different knowledge about the real world. Ilya views language as a natural abstraction of the physical world, hence learning from language could be an efficient way to build up that prior. The strength of this approach is obvious - there are plenty of texts out there on the internet, that make the training process easy, but there are still some questions that remain unanswered. One thing is that, does language contain everything we need? Maybe there are some processes in our brain that we consider to be so natural that we never bother to record them in any texts. Also, generating language to ground truth pairs could be a hard task - we don't have enough ground truth data on the internet. Maybe someone says something wrong about the physical world, and we are unable to validate it.

We might need to learn in a smarter way.

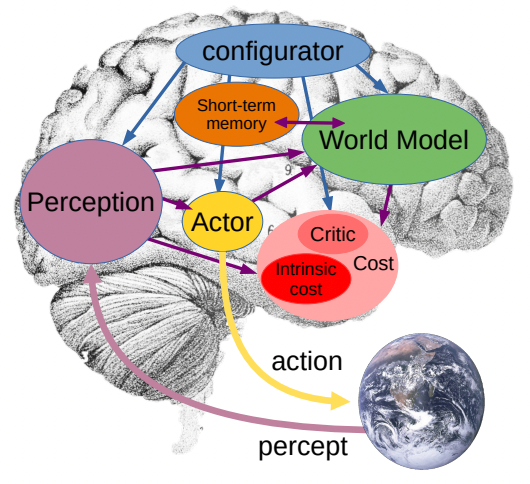

Yann LeCun, another prestige AI scientist, seems to disagree with Ilya's approach. His argument is that when humans convert knowledge to language, a great amount of information is lost, and a great amount of incorrect and redundant information is added, hence large language models will meet their bottleneck very quickly since the prior is not built upon solid ground truth information. LeCun proposes a world model architecture that could possibly optimize the internal learning process of an agent, to utilize the training data more efficiently and accurately. However, a detailed training pipeline is not there yet, and it remains unknown how much this new architecture could help reduce the sample inefficiency in the training data - especially when, it looks like LeCun wants to focus more on video data, which we know is not easy to collect.

We might be seeking the wrong place.

AI scientist Richard Sutton and his student David Silver, are more attracted by reward-based approaches. The underlying principle is that if we design the reward in a smart way - not the inefficient way when humans evolved, but with some more targeted reward signal - we could improve the training process of that prior. In other words, we might be seeking the wrong reward in the past time. However, their article is still too vague about how to design rewards with rich signals. Also, could those rewards be auto-generated? If not, populating those rewards into the training environment could be an extremely hard and costly process.

Some consensus.

Maybe we need better physical simulation.

Why not simulate everything if we cannot obtain them from the real world? That sounds like an attractive approach. Thanks to the recent development of the diffusion model and neural radiance field, we could build a variety of simulated visual data at a lower cost than ever before. What is left to be difficult, is the physical simulation, which is still highly dependent on rule-based environments. There is still much to do to bridge the gap between training in a simulator and execution in the real world for any robot. Also, the cost of maintaining such a simulator could be higher than what we expected.

Do we still need an embodied AGI?

If you reach here, you might have already noticed that, many of those constraints we mentioned above point to a common root cause: cost. A natural question arises: do we really need those embodied AGI if we could have some cheaper alternatives? Taking cooking robots as an example, having a private cooking robot in everyone's home could be very expensive, instead, mass pre-cooked food production is a cheaper alternative. The same argument could apply to self-driving cars. Will people buy self-driving cars if public transport could take us everywhere?

We don't have a concrete answer yet, but I tend to believe the demand for personalized services will always be in an increasing trend. Moving from Yahoo to Twitter to TikTok, we observe that it is always more personalized information channels that win over the less personalized ones. Moreover, nothing more than the story of the iPhone shows us how much new demand themselves could be created.